It was do-it-yourself DNA test kits that helped US police track down the suspected Golden State Killer.

Joseph James DeAngelo was arrested last month after DNA information on a genetic database called GEDmatch allegedly connected him to 12 murders and 50 rapes across California from the 1970s.

In April, police in Ohio used DNA matches, again on a public genealogy database, to identify the “Buckskin girl” – a young woman murdered in 1981

Despite 21-year-old Marcia King wearing a distinctive buckskin jacket on the night she was bludgeoned and strangled to death, who she was had remained a mystery for more than three decades.

The high-profile cases have thrown a public spotlight on the home tests kits offered by the likes of Family Tree DNA, 23andMe, AncestryDNA and MyHeritage DNA, just as they are beginning to explode in popularity.

But the ripple effects of DNA genealogy are also quietly causing seismic revelations in the private lives of families across the world.

As well as offering information on ethnicity, the DNA tests – which cost around $100 – give people the chance to search for lost relatives through DNA matching.

On Ancestry DNA alone, the number of people in its database searching for family matches has skyrocketed to 10 million.

In Australia, children who were given away in closed adoptions have been given fresh hope of finding their birth parents, and vice versa.

Donors who provided sperm decades ago under the promise of privacy are finding themselves suddenly exposed.

Amateur historians simply looking to fill out their family tree are also being thrown some genetic curve balls.

Last month, nine.com.au reported on the case of a Queensland woman who found out through a DNA test kit that the dad she had always known was not her real father.

When Peter Moore, from Lake Macquarie on the NSW north coast, did a DNA test early last year it also led to a shocking revelation that would force him to reassess his entire identity.

Mr Moore told nine.com.au that he wasn’t expecting any big surprises from the DNA test when he took it back in 2016.

The 59-year-old had been researching his family tree for more than 13 years and thought he knew his ancestry inside out.

“I had been a family genealogist for many years and had accumulated 13,500 people in my family tree,” Mr Moore said.

“I had been to family reunions all over the country. I even had a headstone remade for my Irish convict ancestor and organised a family reunion around it. I used to brag about how Irish I was.”

But curious to know where his granddaughter’s and grandson’s olive skin came from, Mr Moore bought a DNA test kit for all of them.

When the results came back, Mr Moore was surprised to get a message from a Sydney woman with an Italian background whose DNA was a close to match to his, close enough to be his half-sister. The woman was a complete stranger.

The woman told Mr Moore she feared she was adopted because her brother and sister always used to tease her as a child that she was.

However, the more Mr Moore tried to find a place for her in his family tree, the less things made sense.

Until eventually, Mr Moore can to the startling revelation that it was not her that had been adopted – it was him.

“One night, when I was looking at my tree and my DNA results I came across the fact that there were no surnames in my DNA matches which matched the names on my tree that I knew intimately,” he told nine.com.au.

“To test my theory I tested my wife’s DNA matches against her side of the tree and sure enough there were surnames there that I was familiar with.

“I had always known that I was born at the Salvation Army Bethesda Hospital in Marrickville. I had Googled it many years ago and all I got was an image of an old building. I Googled it again and all of this stuff came up about forced adoptions.

“The smoking gun was there, it was obvious. I was adopted.”

The revelation rocked Mr Moore to the core.

“I was shell-shocked. All of a sudden my identity was gone. Everything I had known about my life was a lie. It was traumatic to say the least,” he said.

Growing up, Mr Moore’s parents had never given him any reason to think that he was adopted.

But, more than half a century later, a memory Mr Moore believes he must have supressed came flooding back, of himself in a high school science lab testing blood types.

“Everyone was doing to blood types of their parents and coming up with their blood types. I did mine and realised it didn’t add up,” Mr Moore said.

“I didn’t say anything but I waited until after the class and I went up to the science teacher and showed him.

“He looked at it and said, ‘Well, he’s not your father then, you’re adopted’. As blunt as that.”

“I don’t know what I thought. I was probably thinking he was wrong. I remember having an argument with my father a little while later and saying, ‘I’m not your son anyway, I’m adopted’, and immediately feeling guilty. I supressed it all and never thought about it again.”

But, after the DNA test, Mr Moore sent away for an adoption certificate, which confirmed his suspicions.

In a “tearful and painful” conversation with the parents who had raised him, Mr Moore confronted them with the truth in May last year.

“My parents told me that they never wanted to lose me. They burnt the adoption papers when I was a teenager,” he said.

The woman who contacted Mr Moore would turn out to be his sister on his father’s side.

At the same time, Mr Moore began looking for his birth mother, whose name was written on his adoption certificate.

A stroke of luck led to Mr Moore finding one of his brothers on his mother’s side through Ancestry.

Six weeks after finding out he was adopted, Mr Moore was speaking to his brother, and 85-year-old mother, on the phone.

“I found out that my brother had only known about me for three weeks,” Mr Moore said.

“My mother had had a mini stroke before Christmas and became concerned that she might have another one and wouldn’t be able to talk.

“So she confided in my brother and her husband of 55 years that I existed. He promised to track me down – I found him first.”

Soon after, Mr Moore drove up to the Gold Coast to meet the mother and siblings he never knew.

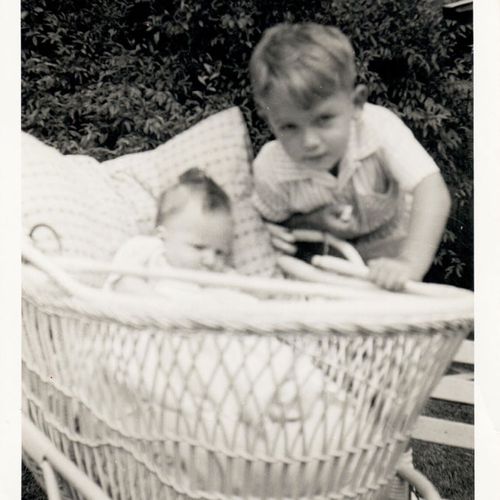

“Meeting my mother was surreal. I was nervous and excited at the same time. All she wanted to do was hold me and look at me. It was a special moment,” Mr Moore said.

Mr Moore has since visited his mother and extended family several times and said he had come to learn more about the difficult circumstances she was in when she gave him up for adoption.

“She was a single mother, newly divorced. She had no support offered from family or from the government. My grandmother didn’t want her to have me,” he said.

“She sent her to Sydney to get rid of me. It was a forced adoption.”

Although his father, from Canberra, has since passed away, Mr Moore has also reunited with the sister who contacted him, as well as his large Italian side of the family.

“I have been welcomed into my father’s side of the family. I can’t say enough how warm they have been to me. There’s been lots of wine and food and laughter,” he said.

“It’s the up-side of adoptions, finding new friends and family. It’s been an exciting journey.”

Mr Moore said he had no regrets about doing the DNA test, despite the dramatic revelations it led to.

“DNA is wonderful. I wouldn’t have known all of this. At the end of the day a lie is a lie and it has revealed it. And I may never have met my mother. I may never have met my brothers and sisters. It’s opened the door,” he said.

Mr Moore said he knew he had been very lucky to have been welcomed with open arms into his “new” families.

“I know my experience is different to a lot of adoptees. A lot haven’t had the success I have had. I have met some very broken people and it’s a terrible shame.

“If anyone has someone knock on their door or ring them up, and say, ‘I am your brother, your sister, your daughter, your son’, I would say to them just welcome them in, open the door. Don’t victimise them a second time.”

Contact reporter Emily McPherson at emcpherson@nine.com.au.

© Nine Digital Pty Ltd 2019

See the video here